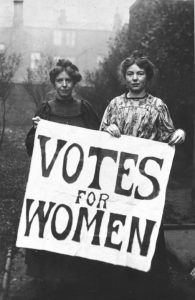

WAND Patron Tracey West gives a summary of the suffrage movement as we celebrate 100 years of The Representation of the People Act, 1918 which was passed on 6 February 1918.

‘Suffrage’ is the right to vote in public affairs and political elections. It commonly marks the long and winding road that describes female emancipation and universal suffrage for women, which is being highlighted throughout February across the country.

WAND are hosting a week of inspiring events that chime with the passion roused within the suffrage movement. It happens to coincide with the centenary of The Representation of the People Act, 1918, the commencement of which finally allowed British women over the age of 30 who met certain property qualifications, to vote for the first time. They went on to exercise that right at the general election later that year.

The suffragettes were a phenomenally fearless and driven group of ladies. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, they rose up in a variety of ways that included lobbying MPs and disrupting the House of Commons and Parliament. By 1903, Emeline Pankhurst, founder of the Women’s Social and Political Union, decided the movement needed to be more radical if change was ever going to come and their campaign became positively militant. Property and art were frequently destroyed and their members were regularly incarcerated. They protested frequently by embarking on hunger strikes, to which the authorities retaliated by force-feeding them; this evil process was only suspended due to the outbreak of war in 1914.

Tragically, suffragette Emily Wilding Davison gave her life to highlight the cause by throwing herself under the king’s horse in the 1913 Derby. Her half-brother, Captain Henry Davison, gave evidence about his sister at the inquest, saying she was, “A woman of very strong reasoning faculties, and passionately devoted to the women’s movement”.

Long before the suffragettes came along, Elizabeth Heyrick was another lady of guts and substance. She was a political reformer in the anti-slavery movement and in 1824 she published a pamphlet: ‘Immediate, not Gradual Abolition’. She campaigned passionately in favour of the emancipation of slaves in the British colonies, thereby rocking the boat and challenging the system. William Wilberforce was a man onside with the idea of change. He batted on the same team and went on to become the voice of the abolition movement in Parliament. Yet commenting about Elizabeth Heyrick, he disparagingly said, “For ladies to meet, to publish, to go from house to house stirring up petitions – these appear to me proceedings unsuited to the female character as delineated in Scripture”.

Emeline, Emily, Elizabeth and countless other women have endured unimaginable pain and hardship as a result of their tireless activism in the fight for women’s rights. They’ve bravely stuck their heads above hostile parapets calling for social reform and trying to evoke positive change. Speaking as one who has tried to do it in respect of domestic violence, I can tell you it usually comes at a price.

History more frequently recounts the actions of suffragettes who were unashamedly physical activists. It talks far less about suffragists, who also campaigned vehemently for women’s right to vote, but they adopted a completely different strategy to draw attention to the cause.

Under the leadership of Millicent Fawcett, a peaceful corps of women were consolidated. Millicent headed The National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies for over 20 years, which was founded in 1897 via the merger of the Central Committee, National Society for Women’s Suffrage and the National Central Society for Women’s Suffrage.

They truly believed they’d achieve their end using peaceful tactics with non-violent demonstrations, via petitions and the lobbying of MPs. Millicent believed that if their organisation was perceived to be intelligent, polite and law-abiding, they’d prove themselves ‘responsible enough’ to participate fully in politics.

Millicent’s peaceful methods were unquestionably pivotal in helping to secure the vote for six million British women and a statue of her holding a placard that says, ‘Courage calls to courage everywhere’ is being erected in Parliament Square, London. She used these words in an address she gave following the death of Emily Wilding Davison.

As history sprinkles a layer of dust on the stories of these important women, we must remember our right to vote was hard won – that ‘X’ really matters.

Suffragettes of Note

Ethel Smyth: composed the suffragette battle anthem, The March of the Women. She responded to Emeline Pankhurst’s call to break a window in the house of any politician who opposed votes for women and along with 100 women, she was arrested and served 2 months in Holloway Prison. When Thomas Beecham went to visit her, he found suffragettes marching in the quadrangle singing, as Smyth leaned out of a window conducting the song with a toothbrush.

Kitty Marion: a successful music hall artiste, she worked her way up from the chorus, to named parts, to stand-in for a lead role, before falling out with her employer. She continued to seek work in the music halls and discovered that some employers expected sexual favours in exchange for the best jobs. Marion became a prominent activist in the suffrage movement, frequently engaging in protests and was arrested numerous times. Her activism led her to be force-fed more than 200 times in 1913 alone.

Edith Rigby: joined The Women’s Social and Political Union and was spat at in the street by her neighbours. She marched on the Houses of Parliament in 1908 and was arrested with 56 other women. She served a month in prison and took part in hunger strikes and was subjected to force-feeding.

Mary Leigh: an active suffragette, was incarcerated at Winson Green Prison. She protested by breaking her cell window, whereupon she was moved to the punishment cell and immediately commenced a hunger strike. Her account of being force-fed is harrowing. She documented: “I was then surrounded and forced back onto the chair, which was tilted backward. There were about ten persons around me. The doctor then forced my mouth so as to form a pouch, and held me while one of the wardresses poured some liquid from a spoon; it was milk and brandy. After giving me what he thought was sufficient, he sprinkled me with eau de cologne, and wardresses then escorted me to another cell on the first floor. The wardresses forced me onto a bed (in the cell) and two doctors came in with them. While I was held down a nasal tube was inserted. It was two yards long, with a funnel at the end; there was a glass junction in the middle to see if the liquid was passing. The end was put up left and right nostrils on alternate days. Great pain was experienced during the process, both mental and physical. One doctor inserted the end up my nostril while I was held down by the wardresses, during which process they must have seen my pain, for the other doctor interfered (the matron and two other wardresses were in tears) and they stopped and resorted to feeding me by spoon.”